Australian democracy’s processes are far from perfect but they are what we have. C. R. (Bert) Kelly, Member for the South Australian Federal seat of Wakefield used them. He addressed very different problems from those current but lessons may be drawn.

Bert addressed the relative decline of the Australian economy. From the wealthiest nation in the world in the late 1800s (Argentina had been number two) we had slipped to a ranking in the middle and late teens. And while it is generally accepted today that our decline was because of unwise regulation of economic activity, especially the barriers to trade, that fact was not widely understood in the 1960s and 1970s before the Hawke-Keating-Howard reforms.

But first something of Bert Kelly’s character.

I knew Bert well and admired him. When in Adelaide I always stayed with the Kellies. He was for me a father figure who put much effort into ensuring that I understood my responsibilities, but the following draws also on another’s assessment[i]. Bert Kelly did not practice religion but was of Methodist stock. He was hard working, principled, and fair-minded. Where he deemed it necessary, he was stubbornly defiant, and he had that way with words that marks effective lay preachers. Public duty was family tradition. He no doubt wished to be promoted to the ministry but never allowed that ambition get in the way of his understanding of obligation to the public. He portrayed opponents as wrong, not evil. Although he certainly made several of them look ridiculous, he was never uncivil. Wilful exaggeration is lying and Bert did not lie. He was self-deprecating to the point of the irritation of his friends, nevertheless, Bert must have realised that he was achieving something worthwhile. Those who listened to him learned to trust him. I am convinced that an exceptional character was central to his achievement.

Kelly was both an unusual parliamentarian and a very successful newspaper columnist publishing over 800 columns in major newspapers under the bye lines The Modest Member and, after he left the parliament, The Modest Farmer. He had penetrating wit used to great effect. He did not practice political one-upmanship and probably would have been little good at it. Every speech, parliamentary question or newspaper column strove to explain rather than to win votes.

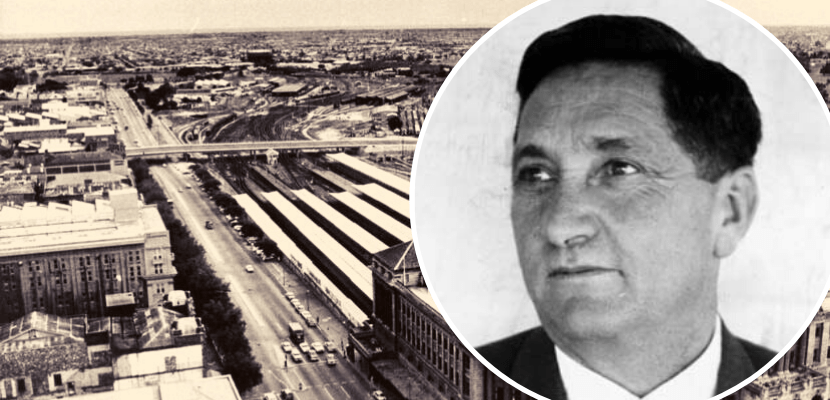

So much for his character and his tools. Bert, born in 1912, farmed successfully at Tarlee north of Adelaide, wrote for farming publications, married the delightful Lorna, won the Federal seat of Wakefield in 1958, was appointed to the Ministry from 1966 till 1969, began his Modest Member columns in the Australian Financial Review in 1969, lost the Liberal pre-selection for Wakefield in 1977 and died in 1997. From 1958 until the late 1970s when the Dry economic-rationalist group emerged, without allies within the parliament, Bert fought high tariffs, subversion of the Tariff Board and many of the more obvious economic inefficiencies and injustices. Continuous attempts to dismiss him as a crank largely failed, I think because of the way he went about his task. There may be lessons here for those who argue the case for return of our liberties after the corona virus.

After the 1961 election the Coalition had a majority of only one. Jack McEwan, Minister for Trade and leader of the Country Party demanded protection of Australian industry. There was limit to how far Menzies could defend Kelly’s right to express his opinion without dividing the Coalition, and Menzies made this clear to Bert. One day in the Party Room Menzies allowed McEwan to bucket Bert and then did so himself. When that happens one can but sit there and take it. I know! After the 1964 election, however, Menzies was more supportive.

I won’t describe Bert’s mammoth analysis of the use of the Temporary Assistance Authority’s (fortunately abolished in 1984) powers to reverse Tariff Board decisions, and other brave forays within the House. One has to have been a politician to fully appreciate them. By them, Bert won the respect of many journalists, academics and senior civil servants. He cultivated the consequential contacts and, within the limits of the proprieties, they kept him briefed.

An example of his writing tells more than description. It followed his visit to two factories in Bombay, one reconstituting skim milk:

I asked them if they had any troubles and they said only one: ‘We like your skim milk powder, but we have difficulty in getting enough foreign exchange so that we can buy enough of it.’

The other was a cotton sheeting factory:

‘Only one,’ they said. ‘You people in Australia put a tariff of 55% against our sheets so that we can’t sell them in your country and this prevents us from earning foreign exchange.’

I find it so difficult to see the sense in all this. The Australian dairy farmer can’t sell his skim milk powder, the Australian housewife has to buy dear sheets, the Indian kids can’t get milk and the efficient Indian sheet factory can’t make sheets. And this is brought about by [our] good and wise Government.

I choose an example of his humour from a speech to the Council of Europe. Laughter caused chaos in the translator service.

The story was about that legendary Australian couple Dave and Mabel, who came to Sydney from the bush and stayed at a hotel where the plumbing was much different from what they were used to at home. At 10 o’clock Mabel complained of feeling thirsty so Dave went out and got her a glass of water. At 11 o’clock she was still thirsty so he got her another glass of water. At 12 o’clock the same thing happened and when Dave this time came back with an empty glass, Mabel asked ‘What’s wrong, Dave?’ and he replied ‘There is someone sitting on the well!’ And after about three minutes, when the laughter had died down, he added `And you sods are sitting on our well’.

Bert changed opinion by explanation. He employed laymen’s language for what was in reality quite basic micro-economics and to alert people to unfairness (inequity). He must also have encouraged and cheered others who were making principled stands, such as senior civil servants at the Tariff Board and several academic economists. Across the House, even some Labor members understood.

I never heard Bert admit his success but in retirement he must have appreciated that he had been highly influential. Enough of us told him so and at a huge gathering in Melbourne, which was the home of most of his opposition, honoured him. Several captains of once-protected companies attended. At that he was, as usual, funny and self-deprecatory. He cared for his nation.

Can you appreciate why so many of us loved him?

[i] Shaun Kenaelly