This article originally appeared in The Spectator Australia.

The Australian government’s proposed ban on live exports, and subsequent passage of a policy to phase out the industry by 2028, has sparked renewed debate and division across the nation. This initiative was precipitated by alarming footage revealing mistreatment of Australian cattle in Indonesian abattoirs, which led to a temporary ban on live exports to Indonesia in 2011. Subsequently, the government introduced stricter regulations to improve animal welfare standards, including enhanced transport conditions and handling practices mandated by the Australian Standards for the Export of Livestock and the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS).

The Labor Party’s endorsement of the live export ban, aimed at fulfilling an election promise, has stirred widespread dissatisfaction among farmers. This departure from their historical support base, rooted in events such as the 1891 shearers’ strike that played a pivotal role in the party’s formation, reflects a shift influenced by activist pressures and the electoral threat posed by the Greens. This move underscores concerns that Labor is prioritising urban, left-leaning agendas over the economic and social realities of rural Australia.

The implications for rural communities, particularly in Western Australia, have sparked strong opposition. Western Australia, a major hub for live exports, faces significant economic repercussions if the ban proceeds. The sheep industry alone contributes substantially to the state’s economy, valued at $1.35 billion according to recent estimates from the Western Australian government’s Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. The potential loss of this industry, compounded by declining exports and economic pressures, threatens livelihoods across the agricultural sector. Sheep prices in Western Australia fell to $90 per head over the past two years, reflecting broader industry challenges. The ban will also lead to the contraction of sheep flocks in the state by around 30 per cent, while Western Australia’s $655 million merino wool industry would also shrink dramatically (currently comprising half of the state’s sheep industry).

Farmers and industry leaders have expressed scepticism regarding the adequacy of the government’s proposed $107 million compensation package. They fear it will not sufficiently mitigate their losses, with only $94 million earmarked for farmers after accounting for government implementation costs. This concern is compounded by the complexity of transitioning to onshore meat processing, which faces challenges such as market saturation and price competitiveness.

Criticism from political circles includes concerns about Labor’s departure from traditional working-class interests to policies influenced by activist agendas and electoral dynamics. This shift underscores the divisive nature of the debate, with farmers arguing that such policies prioritise urban concerns at the expense of rural livelihoods. Recent comments by a Greens Senator that, ‘The industry is right on one thing … animal welfare campaigners won’t stop at just the live sheep industry…’ have further frustrated farmers. These sentiments again highlight a widening urban-rural divide over policy decisions affecting primary industries.

Australia’s rigorous animal welfare standards and regulatory frameworks are globally recognised, ensuring humane treatment throughout the export process. The country’s commitment to ethical standards, including welfare guidelines from paddock to abattoir recommended by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), sets a benchmark exceeding international norms. Moreover, Australia’s control over its supply chain ensures adherence to these standards, crucial in maintaining its reputation in global trade. In order to obtain an export licence from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, exporters must demonstrate they have control over ‘every link in the supply chain’.

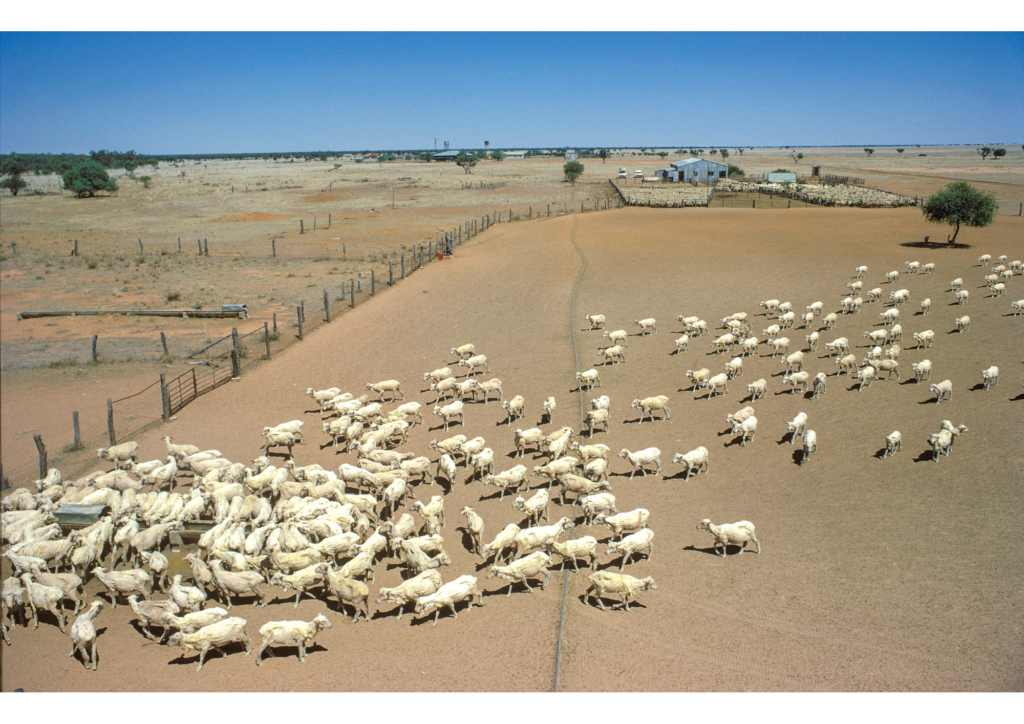

Australia’s industry practices, including strict export bans during the northern hemisphere summer and meticulous transport conditions, contribute to remarkably low mortality rates during shipping, currently at a record-low of 0.14 per cent. Proponents argue that live export supports sustainable farming by managing herd sizes and reducing overstocking risks, benefiting both animal welfare and environmental sustainability. Overstocking in grazing areas can lead to soil degradation, erosion, and increased risk of disease outbreaks, impacting agricultural productivity and environmental health.

Australian farmers have increasingly turned to cropping as a potentially more profitable alternative to sheep farming, influenced by projections and statistics over the last two decades. This shift reflects broader economic uncertainties surrounding the live export ban, prompting farmers to consider downsizing operations, reducing lamb numbers, unnecessary euthanasia to maintain healthy herd sizes, or leaving the industry altogether due to economic pressures and regulatory uncertainties.

The proposed ban is likely to increase demand for live exports from countries with lower standards than Australia, posing unintended consequences to animal welfare and sustainability. This scenario underscores the complex interplay between ethical imperatives and economic realities in shaping policy decisions. Animal welfare is a crucial concern for all stakeholders, as evidenced by Australia’s rigid regulations and commitment to animal welfare standards. Stakeholders recognise that reducing animal mortalities during transportation not only upholds the welfare of animals but also preserves economic viability. To paraphrase a vet on board a live export ship: ‘Dead stock does not generate revenue.’

The economic and social impacts of the proposed ban extend far beyond the immediate loss of export income, affecting jobs, businesses, and community stability. Local industries, schools, clubs, and individuals that rely on the economic activity generated by the livestock industry would also feel the impact, underscoring the interconnectedness of rural economies. As former Nationals MP James Brown has said, ‘It’s not just the shearer or the truck driver; it’s also the hairdresser and the fish and chip shop operator.’ For instance, in the Shire of Narembeen in the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia, approximately 400,000 sheep support around 180 businesses and contribute almost $19 million to the local economy. Thus, finding a balanced approach that preserves both animal welfare and economic vitality remains imperative.

Labor’s belief in expanding the local meat production market includes promoting Halal-accredited abattoirs and ensuring competitive local prices. This approach aims to capture and expand domestic markets previously supplied by live exports, aligning with efforts to bolster onshore processing capacity and employment opportunities in regional areas. However, challenges such as market competition from existing overseas markets and pricing dynamics pose significant hurdles to achieving full market self-sufficiency within the proposed four-year timeline.

Hurdles to onshore meat processing include existing months-long waiting times at abattoirs and the higher prices wethers attract overseas. Eighteen-month-old, wool-growing wethers are typically shipped overseas due to the low price they attract domestically compared to lamb. The demand for Halal meat in overseas markets, traditionally supplied through live exports, presents additional complexities in transitioning to onshore processing. However, according to a document from the Western Australian Parliament, a large proportion of Australia’s meat-exporting abattoirs employ Halal-accredited slaughtermen, while Middle Eastern nations already import chilled meat from Australia. Nonetheless, competing with established international markets requires competitive pricing strategies and infrastructure investments to enhance domestic processing capabilities.

From pasture to politics, Australia’s proposed ban on live exports has stirred nationwide debate and division. Initiated by distressing footage of cattle mistreatment in Indonesian abattoirs, it led to stringent reforms. Labor’s endorsement, driven by electoral promises and pressures, has alienated its rural base rooted in historical solidarity. The ban’s economic impact, particularly in Western Australia’s sheep and wool industries, threatens livelihoods and community stability. As Australia navigates ethical imperatives and economic realities, balancing animal welfare with economic vitality remains paramount.