So, shortages. You may be familiar with tales of bread lines during war time and in the Soviet Union, and, in recent years, with photos of empty supermarkets in Venezuela.

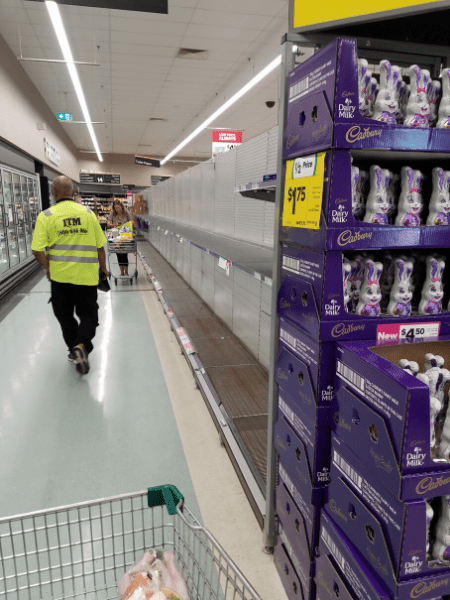

During April 2020, certain shortages started occurring in Australia. Spurred on by alarmist headlines of the impending COVID-19 pandemic, people started buying larger amounts of certain goods, particularly toilet paper, hand sanitiser and facemasks. As this behaviour was reported in the media, more people went out and bought extra for themselves too, afraid of “missing out”. Before long, certain supermarket and pharmacy aisles were perpetually stripped bare.

People were accused of “panic-buying” or “hoarding”. Fights broke out when new shipments arrived.

Shortly after, supermarkets introduced rationing (transaction limits) and announced “community hours” (designated shopping hours for pensioners and the like) in order to try to ensure everyone gets their “fair share”.

Did these measures work as intended?

During early April 2020, when I managed to get my hands on a 24 pack of toilet paper, it was because I was ready at the door when Coles opened. Already the shelves were half empty, but I was delighted to find that the 24 pack was on sale, at 25 percent off. What a win! But, I also scratched my head as to why on earth it was on sale during a shortage – bearing in mind that sales are designed to move excess stock.

It struck me that the transaction limits are a very crude tool. After all, the checkout machines do not discriminate against someone buying a 4 pack versus a 48 pack. Likewise, those with hoarding instincts could easily run back in and buy another pack in a separate transaction. Or bring your whole family so they can each buy a packet. Or visit multiple supermarkets in a single outing. So much for limiting community interaction.

With Western Australia’s (now-repealed) transaction limits on alcohol, bottle shop owners voiced their concern about this exact phenomena happening; people, so desperate to stock up their liquor supply, were making trips to multiple bottle shops so they could “legally” buy their shopping quota, one by one. Or, visiting the bottle-o every day. And up goes the risk of either catching the virus or spreading it.

Economists call this unintended consequences. Adam Smith would surely have been turning over in his grave, knowing that it was the invisible virus, rather than hand, that dominated.

What if there is a better way than simple transaction limits? Let me introduce you to a different type of rationing that alleviates or at least supresses, hoarding, plus bring a few extra positives.

It is called letting prices rise (or fall) to reflect supply and demand.

Prices are not just random stickers on product shelves. They are not set arbitrarily; they are in fact signals that communicate what is what where and how urgently.

Anyone who has studied Econ101 should understand this. However, in rapidly changing scenarios, and particularly in crises, price spikes are often met with extreme scrutiny and disdain. Should the price spike be “too much”, it is called “price-gouging”, which has an ugly ring to it.

It is not surprising to me that supermarkets went with transaction limits and community hours. They both sound rather nice and benevolent. If they had dared raise the price of toilet paper to reflect the rampant demand, they would undoubtedly have copped the wrath of politicians and other so-called morality experts.

Limiting how many packets of toilet paper you can buy versus raising the price may have a similar effect, but let’s entertain the notion of increasing the price instead.

Back in the good old days, a 24 pack of toilet paper cost around $12. That’s not a huge amount of money. Those who engaged in hoarding early on probably didn’t think twice about buying as much as they could humanly carry. Toilet paper doesn’t expire, after all, so unless you are space-poor, why not buy 500 rolls?

But if the price was doubled to $24, perhaps people would be more prudent with their money. OK, maybe I won’t quite buy 500 rolls. Maybe I’ll stop at 250.

If it was $48, then I’d get 125. And so on.

Knowing that the stuff was also now rather expensive, perhaps people would use less of it, too. I won’t go into details of what that entails, but I’m sure you get my drift. Professor Michael Munger describes this phenomenon in a recent podcast.

If supermarket chains had raised their prices to ensure adequate stock levels, then that makes a multiple-transaction shopping spree redundant.

The true crowning glory of letting prices rise, though, is the fact that it would send a signal to producers and would-be-producers that there is profit to be made. This product is in high demand, so we should make more of it. Depending on how long producers deem this scenario to last for they would need more equipment and, perhaps more important, more workers for their increased production schedule. With so many people now out of work, new jobs would be welcome.

Starting up new factories, or even just increasing productivity, might not be financially feasible for toilet paper producers. The fixed costs may be too high to warrant it. But the principle still stands, though perhaps more so for other products such as facemasks.

Sadly, you can see how the mainstream media view price spikes in this ABC interview. This example is on how the price of facemasks went from $40 to $800 per box. The steep increase is actually a rationing mechanism that ensures against hoarding, as well as making sure that facemasks go where they are most needed; to the frontline healthcare workers.

At least we escaped having our political overlords setting price-ceilings on toilet paper. I have no doubt that they would have relished the opportunity if a supermarket had dared attempt it. The media would also jump in, posting headlines declaring moral outrage. We saw it when Uber first introduced their surge pricing mechanism.

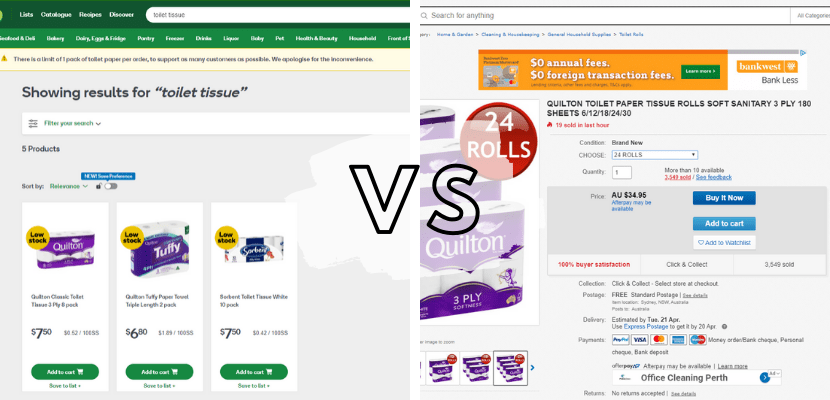

Perhaps the supermarkets are just worried about maintaining their community goodwill. Still, it looks like they are missing out on sales. Supermarket shelves may now be restocked, but, at the time of writing, transaction limits are still in place, toilet paper is not available for home delivery and the biggest packs on Woolworth’s website is a measly 10 for $7.50. Meanwhile, over at eBay, the same product is selling for a premium with no limits on the amount you can buy and sales are flying through the door.

Seems to me that there are plenty of willing buyers at high prices, and that has brought a plethora of new sellers into the market. Who would have thought?

Despite our politicians’ dreams of “hibernating” the economy – coined “cryonomics” – now, more than ever is the time to let prices do what they do best: signal what is scarce and what is not.

If you want more information on how prices are actually information carriers, you should read my colleagues’ paper on Western Australia’s electricity market.