At the end of April, the Leader of the Opposition announced plans to boost the pay of 100,000 childcare workers by 20 percent, through a taxpayer funded subsidy which is estimated to cost $9.9-billion over the next decade. Naturally, unions in adjacent sectors have since demanded that these taxpayer-funded pay rises also be extended to their respective industries.

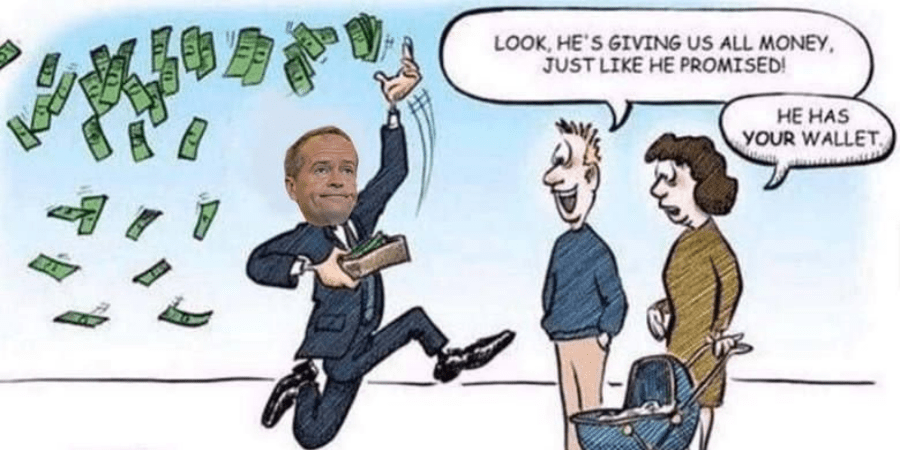

In attempting to justify the policy, Bill Shorten highlighted exactly why the childcare market finds itself in a state of such disorder:

“The fact is, childcare has a lot of government funding so when the government funding is tight there is no money for wage rises.” – The Australian

The quote tracks the long-standing approach of the state in its approach to markets – create a distortion through intervention, try to rectify the distortion with more regulation (funded directly or indirectly through the taxpayer), then repeat this cycle and marvel at the complexity and inefficiency of the resultant market conditions they’ve created.

Bad regulations aren’t fixed by piling more regulations on top of them. It is true that in some cases, wages no longer reflect the qualifications and skills of childcare workers. Yet this, and the malaise of both supply and demand problems which exist within Australia’s early education system, can be attributed to the layers upon layers of red tape imposed on the sector over the past decades.

The rollout of red tape over time across the childcare sector culminated in the introduction of the National Quality Framework (NQF) in 2012. One of the primary features of the NQF is the minimum qualification standards and staffing ratios, which were enforced in an effort to improve the educational and behavioural outcomes of children in these institutions. Despite the introduction of the onerous regulatory framework – which drove up costs for childcare providers and reliance of the sector on government support – there is very limited evidence that NQF rules result in the desired improvements.

The fact of the matter, however, is that stipulating unnecessary qualification requirements for childcare workers, creating an overqualification problem, and then attempting to remedy this the through industry-wide wage fixing creates an unsustainable market system. Perhaps, the response to the supply side issue in the childcare market should not be met with calls that staff are underpaid, but instead overqualified. The majority of parents are impartial as to whether the carer of their child has completed tertiary education, and yet under the NQF, parents of all income levels have been forced to pay a premium for the diploma-level qualification prerequisites for staff.

Policies such as these disproportionately affect low-income households, who, despite receiving generous government subsidies themselves, have faced an approximate 50-percent increase in out-of-pocket costs for childcare fees since 2012. These demand-side subsidies which are currently available for parents cost taxpayers around $7-billion in 2018, and will almost certainly rise exponentially under the proposed reforms.

Despite the rhetoric of our politicians to cut costs-of-living, give families a “fair-go” and invest in the future, none of these proposed changes actually address the underlying inefficiencies which plague the sector. This latest policy proposal is just another example of the market-meddling all tiers of government engage in, which taxpayers are forced to fund when the intervention inevitably fails. In WA we see this with energy, housing and public transport – just to name a few.

The other issue that remains is that if the government starts setting wages in the childcare sector, where does it stop? Many construction and healthcare workers are on similar wage rates and possess equivalent qualifications – should their wages be paid by taxpayers too? Addressing these issues, as well as scaling back burdensome regulation and red tape from successive decades of persistent government intervention in across the whole economy, are the problems the next generation of free-market leaders will undoubtedly face. It is only with a sound understanding of market mechanisms and classical liberal principles that we can prevent Australia spiralling into a quasi-socialist state.